Mexican waves to heatwaves: How hot is too hot to play football?

With temperatures in the UK soaring to record levels and the Met Office issuing its first ever red warning for extreme heat, what effect will these extreme weather events have on the beautiful game?

Effects of heat on sport performance

The 2022 World Cup will be the first of its kind, being played in winter rather than its traditional summer slot due to extreme summer heat in the Middle East. But we have seen heat be a factor in previous World Cups – for example, the 2014 tournament in Brazil saw the use of scheduled water breaks for the first time. These stoppages occurred in each half when games exceeded a stifling 34˚C, which we are sure you’ll agree is a pretty tough temperature for a kickabout.

Playing in extreme heat can have serious impacts on athletes, with outdoor physical sports in heat above 30˚C leading to symptoms such as severe dehydration and heat stroke. This, coupled with the reduced match-fitness of players after lockdown, led the Premier League to implement scheduled water breaks in matches during ‘Project Restart’, with games happening in a condensed schedule and in the summer months.

How hot is too hot to play football?

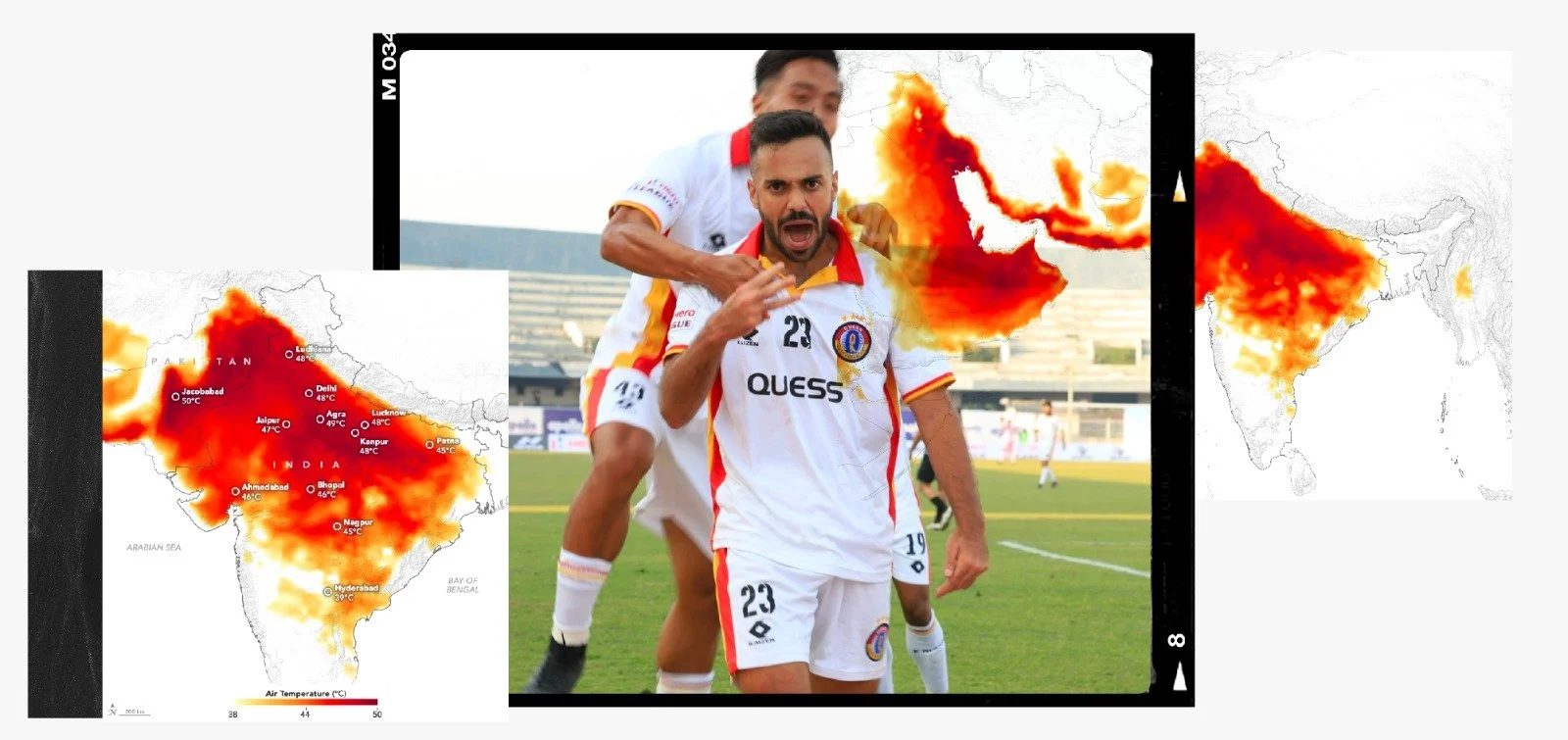

India’s I-League, one of the two co-existing top divisions in Indian football, recently faced a situation leagues above anything faced by PL ballers. A succession of heatwaves since March resulted in temperatures in April and May soaring to the mid-to-high 40s˚C, reaching as high as 49C in Delhi. That’s about 10˚C hotter than the highest temperature ever recorded in the UK. This isn’t just because India tends to have a warmer climate than the UK – it was exceptionally early for the heat to arrive, and it was the country’s warmest March on record. You can see just how much hotter March and April were in the Southern & Western Asia region in the tweet below.

The map above is called a temperature anomaly map, which shows how much warmer or cooler the recorded temperature is than the average – in this case, the darker red the area is, the hotter than usual it is. A more literal kind of heat map than the ones we see from Opta…

You might think that these are the kind of conditions where games would be postponed – however, the Football Players Association of India (PFA India) took to Twitter to voice their frustration and concern towards the I-League for continuing to have matches kick off at 3pm.

Never mind marauding from right-back, the advice from health authorities in many of the affected areas was to stay indoors, with health risks from the heat including dehydration, heat cramps, heat exhaustion and heat stroke. These temperatures are well above the 33-35˚C point where playing sport becomes a serious problem.

It’s clear then that exceptional heat, like any form of extreme weather, is bad news for football, whether it means games are played at a lower intensity and so are less entertaining for spectators and more exhausting for players, or if it is simply not safe to run around in the sun for 90 minutes and so games are postponed. The problem is, climate change is making these extreme weather events more likely and more intense, and human activity is to blame.

Positive Feedback Loops - Why Do They Matter?

What’s more, extreme heat events can contribute to what scientists call a ‘positive feedback loop’. Unfortunately, this kind of positive feedback has nothing to do with a pat on the back from your manager – a positive feedback loop is a complicated part of climate science, but it is essentially an event that accelerates a temperature rise.

In this case, higher temperatures in India meant that people used more air conditioning to keep cool, which uses a lot more electricity. This upshot in demand resulted in energy shortages, and consequently India upped coal production to record levels to keep pace. Burning coal releases greenhouse gases that contribute to climate change and so make those very heatwaves more likely to occur.

It is like being 1-0 down midway through the second half, pushing for an equaliser and conceding a goal on the counter-attack, and then later being relegated on goal difference.

India’s footballers rightly highlighted the dangerous health implications of extreme heat for athletes. These extreme weather events have all kinds of implications not just for the beautiful game but for everyday life as they become more frequent and more intense.

Football must start making tackling climate change an absolute priority. The implications for the game are severe if action is not taken. In the UK, FFF are leading a group campaigning to have environmental sustainability built into football governance, to help protect football clubs from extreme weather events and also to reduce the game’s impact on the climate. We’re in Fergie Time, but there’s still a chance for that last-minute winner.

Comment from the author and FFF:

It’s also important to consider geographical contexts other than the UK when we talk about the impacts of climate change, as it is often the poorest and more marginalised people in the world who face the harshest impacts, not just because many poorer countries have tropical or sub-tropical climates, but because of socio-economic factors – for example, poorer women in India are at higher risk of heat-related health impacts because they tend to stay at home doing work such as cooking in houses without air conditioning. It would take 5 Earths to support the human population if everyone’s consumption patterns were similar to the average American… but only 0.7 Earths if everyone lived like the average Indian. Countries in the West have a responsibility to transition to sustainable means of living as fast as possible due to the impact of our lifestyles.